Energy prices have been soaring. Myriad governments have acted. Interventions have included nationalizing energy production, windfall taxes, and energy price caps.

Australia is no exception. The Federal Government has moved to cap gas and coal prices. The industries have described this as a ‘declaration of war’, signalling they will campaign against the policy and the government.

The policy itself involves capping gas prices at $12 per gigajoule, which is less than half the wholesale gas price. Similarly, the policy caps thermal coal prices at $125 per ton. This too is less than half the market price. These measures are supposed to only last 12 months. But, there is scope for extension.

The government also signalled additional support for “vulnerable” Australians and funding to support renewables stability through (inter alia) battery technology.

The government’s goal is to curtail energy price increases. But, the policy has significant risks and is ultimately harmful.

The policy could crunch current supply

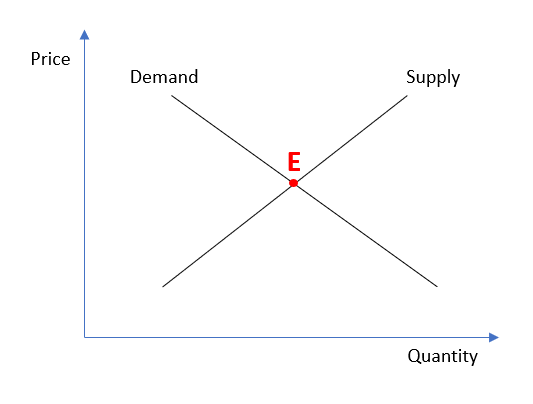

The logical reaction to a price cap is to produce less. This is a relatively straightforward function of supply and demand. In a free market, there is an equilibrium price at which supply equals demand. This is the point at which the marginal benefit of consuming one more unit equals the marginal cost of producing that unit.

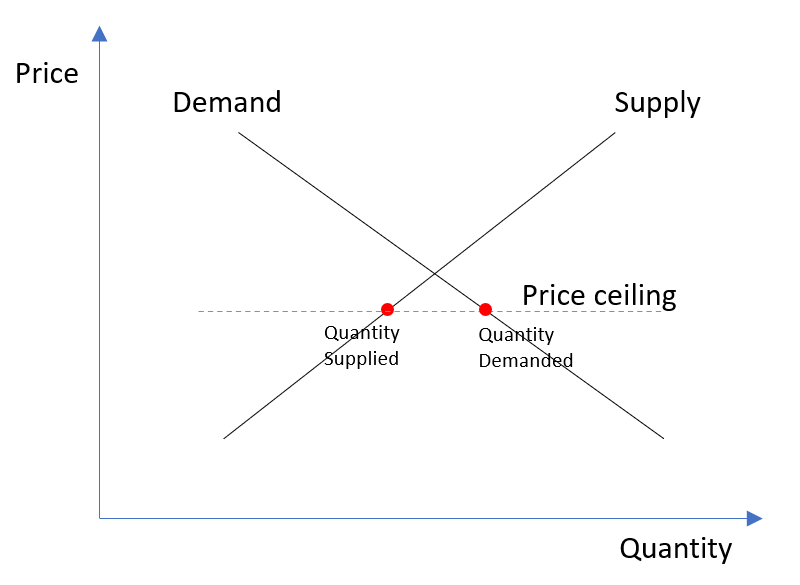

A price ceiling interferes with this. This is because each additional unit of production is more expensive than the last. Think of it this way: Some coal mines are in a convenient location, close to transport and with few environmental issues. Some coal mines are far from freight lines and require substantial remediation and labor costs. The marginal cost of producing from the former is much below that of producing from the latter. The latter is viable only if the coal price is high enough. Therefore, if the price ceiling is below the equilibrium price, producers will simply cut production by furloughing or scaling back expensive production sources.

A temporary price ceiling adds another wrinkle. Producers know that the price ceiling cannot hold. They know this for two reasons: (1) the government has said so, and (2) the fall in both current and future supply will cause too little energy supply, which will force the government to remove the ceiling. This has parallels to when a currency peg breaks. Thus, energy producers would further scale back production until the price ceiling disappears so that they can capture higher prices in the future.

No incentive to save energy

The price cap also provides no incentive to save energy. If energy prices fall, and energy becomes cheaper, consumers will simply demand more energy relative to what they would have saved (see above). This – ironically – can exacerbate the supply and demand imbalance.

It would be more efficient for the government to at least consider subsidies that reduce in magnitude with energy consumption, meaning that high energy consumers pay a higher marginal cost per unit consumed than do low consumers. A simply price cap would not achieve this.

The policy will deter future production

The price caps will also reduce future production. As indicated above, producers have limited incentive to supply more energy at price-ceiling prices. This will also deter future production.

- Future production is inherently more expensive now than using existing production. Thus, if a price cap would deter existing supply, it would tautologically deter capital expenditure to create more redundant supply. This is especially since it would be one of the more expensive ways of increasing production (relative to using existing capacity).

- The spectre of a price cap reduce any upside from investing. Commodity companies require good times to offset bad times. While Newcastle Coal prices are currently over $400 per ton, they were below $60 per ton in early 2020. Profits in high price periods offset losses in low price periods. This applies across all commodities. The price caps undermine the commodity business case, which deters production.

Some might celebrate a move from fossil fuels to renewables. However, there are two main caveats: (1) phasing out fossil fuels is different from immediately and dramatically cutting energy supply without an alternative plan, and (2) if price caps impact commodity companies, renewables firms might well infer that they might be a future target. This has been an issue with the UK windfall taxes. In turn, it is not obvious that renewables firms would step in to fill the gap in energy generation.

Price caps – and de facto price caps – have gone badly before

Price caps have frequently had harmful consequences. A recent example is the UK windfall tax on energy producers. This has parallels to a price cap in that it reduces the net income from producing energy. The windfall tax would impose a 75% tax rate on oil and gas companies. The tax was originally to end in 2025. But, then was extended to the end 2028. It is not clear whether it will be extended again.

In the UK, investment has fallen as a direct result. TotalEnergies pulled its North Sea investment due to the hike. Shell is reviewing GBP 25 billion of investment in the UK energy system and indicated that it might have to invest less. North Sea capital expenditure is projected to decline. Producers are pushing for a price floor to compensate for the windfall tax.

The EU has also had issues. France imposed a price cap, which undermined energy producers’ profitability and triggered full nationalization of some energy companies. This ultimately leads to inefficiencies given the well documented underperformance of state owned enterprises. It also simply shifts the costs of running a loss making company onto the tax payer. Germany has had similar issues with nationalization, albeit with slightly more complex facts.

The government needs to think in carrots not sticks

The EU, UK, and, now Australia, have focused on penalties. These are windfall taxes and price caps that harm business. A more efficient and business friendly way to help the situation is with carrots.

Government could incentivize new energy supply. Rather than hitting existing revenues, thereby making capital expenditure impossible, the government could provide cheap debt for projects that increase renewable output or firming. Government could provide incentives – perhaps in the form of construction grants – for energy producers that increase either supply or energy efficiency. Government could resurrect generous solar subsidies for households. All these factors could both increase growth (i.e., through construction) and increase energy supply.

Government could also look to nudges for consumers. Government could provide small incentives – perhaps paid directly into the person’s bank account – as a reward for energy savings. This small nudge need not be large or economically meaningful. But, it can incentivize the marginal consumer to save energy, thereby reducing price pressure.

The energy price caps have not encouraged investment and have potentially deterred it, as indicated by companies’ reticence to invest in the UK.

This is in addition to the implicit increase in sovereign risk coming from such price caps. After all, of energy is subject to a price cap now, who else is deemed essential. Journalists? Lawyers? Doctors? Will they now also be subject to a cap on their fees?