If it feels like the US is lurching from debt crisis to debt crisis, that might be because it is. At the time of recording, congress is considering whether to raise the “debt ceiling”. Again. The debt ceiling is the limit on how much the US government can borrow overall, including to satisfy already approved expenditures. The debt ceiling currently sits at $31.4 Trillion. The government currently is looking to raise the ceiling so that it can borrow more in order to fund new and existing expenditure.

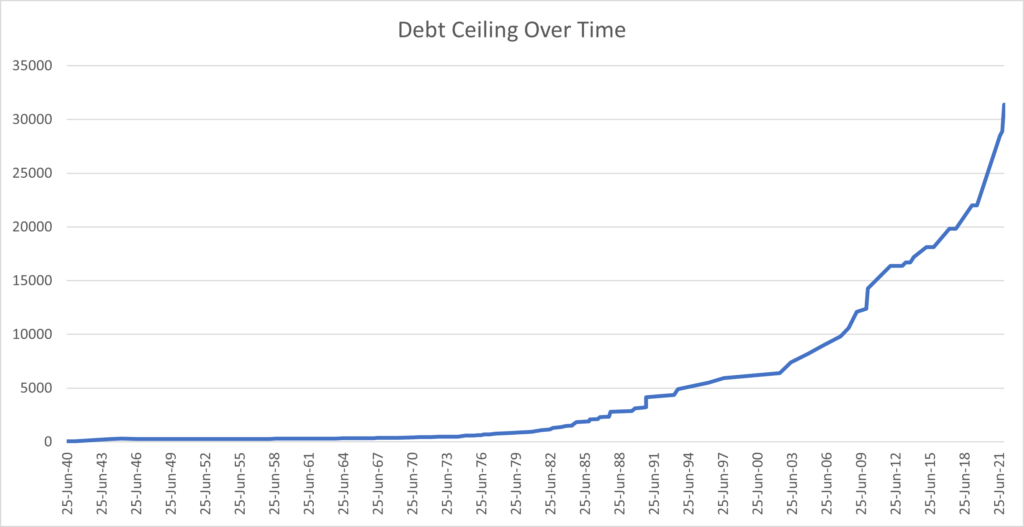

This is not the first time we have been in this situation. Debates over the debt ceiling occur almost every year. Indeed, by the time you see this, we might have moved onto yet another debt ceiling, well above the $31.4 trillion limit that currently exists. Indeed, the debt ceiling has increased nearly exponentially since the 1940s.

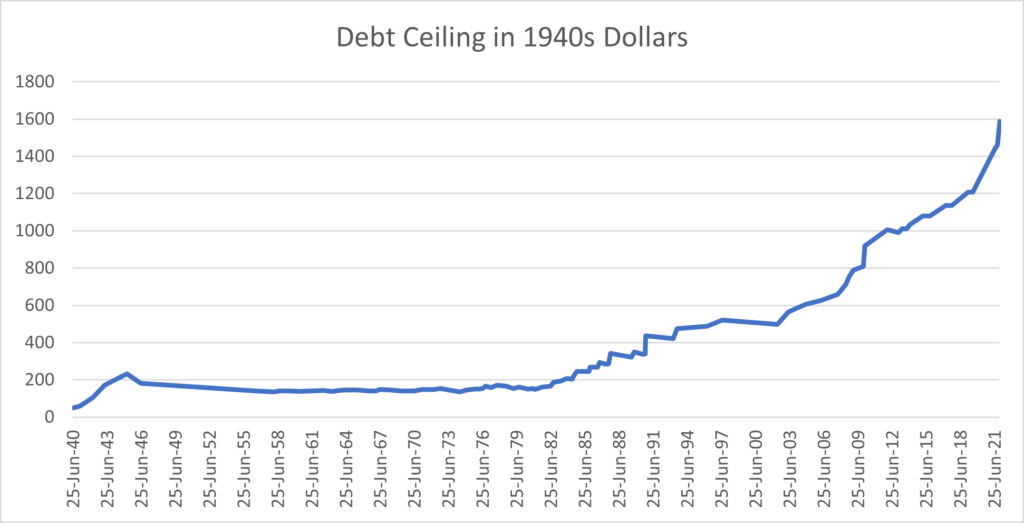

This is not just in ‘nominal terms’. Even after adjusting for inflation, the debt ceiling has increased monumentally. The increase in debt cannot merely be explained by the US dollar devaluaing.

Let’s explore the debt ceiling further.

How did we get here?

The US did not always have a debt ceiling. Before 1917, there was no debt ceiling. However, a debt ceiling emerged in 1917 with the Second Liberty Bond Act. This solidified in 1939 with the Public Debt Acts. Henceforth, the US was to have a form of Debt Ceiling, even if the exact parameters changed over time.

The US had moved away from a Debt Ceiling in 1979. The Gephardt Rule deemed the debt ceiling to increase with each budget. However, congress repealed this rule in 1995. This has exacerbated debt related concerns, leading to myriad stand offs over the debt ceiling.

The current approach means that – in the United States – congress must pass both a budget and a debt ceiling. That is, congress can approve expenditure that is not funded either through revenue or through existing debt provisions. Conversely, congress can increase the debt ceiling above its present requirements, or even suspend the debt ceiling. In practice, this often means that parties tussle over both the budget and over the debt ceiling.

What happens if there is no agreement?

Congress might not agree on a debt ceiling increase in a timely manner. If there is a protracted impasse, this can trigger significant consequences. If the impasse persists, the US might default on its debt. Let us explore some of the ways that congress might manage debt related disagreements.

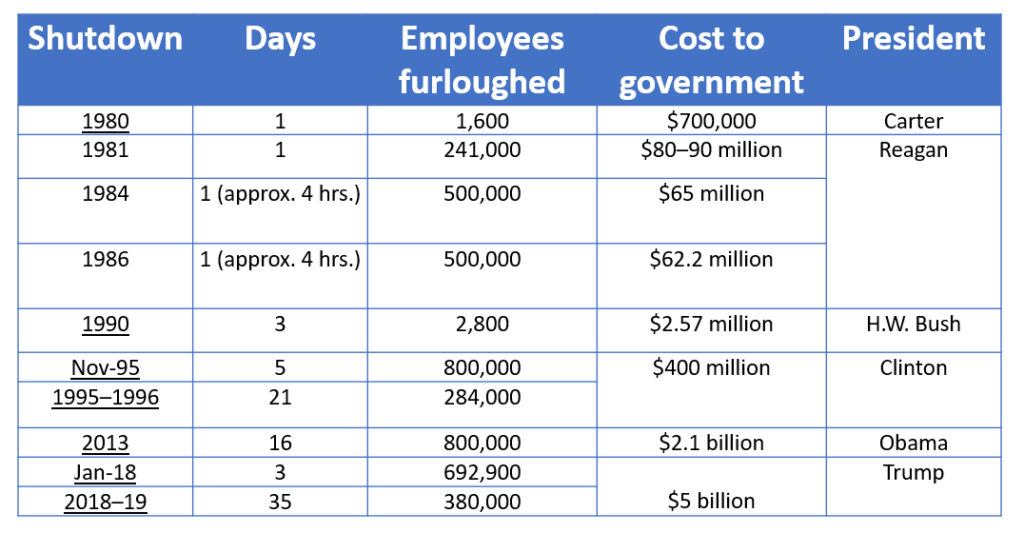

- Government shutdown: A government shut down involves furloughing workers and shutting down various facilities. The furloughed workers are ordinarily not paid during the shutdown but are awarded back pay, where relevant. Contractors are not paid. This can save money in the short term. However, it is costly thereafter. The costs involve dents to the US’s reputation, back pay, rectification for deferred work, overtime when workers ultimately need to catch up on work, and revenue and productivity foregone. Shut downs have been relatively common.

- Extraordinary measures: Treasury has several possible extraordinary measures available. These often involve deferring savings and investment. For example, they can include suspending investments in the Thrift Savings Plan for the retirement fund for federal employees. However, this is relatively short term as treasury would ultimately need to catch up on the foregone investments.

- Sales: The government could sell assets in order to meet short term requirements. For example, the government has sold gold. However, in theory, the government could sell myriad other assets if necessary.

- Money printing: In theory, the US government could print money in order to make payments. However, this would damage government credibility, set a dangerous precedent (i.e., the other party could attempt to orchestrate it), undermine Federal Reserve independence, and be inflationary.

- 14th Amendment: It is possible that the idea of a Debt Ceiling is unconstitutional. However, this is unsettled and would ultimately be for the court to determine. The logic is that, under the 14th Amendment, the debt of the United States “shall not be questioned”. This is sometimes taken to mean that congress cannot take measures that would prevent the government from paying debt (i.e., where it must raise new debt in order to pay for existing unpaid obligations). However, it is not clear that merely refusing to raise the debt limit would violate the 14th amendment. And, in any case, this would be a matter for the courts to determine.

If the impasse persists, the US government could default on its debt. This would be highly costly as it would cause the US’s credit rating to decline. In turn, this would increase the required yield (and interest rate) on government debt. This would make funding the government more costly both immediately and, especially, for future generations.

Why is there a debt ceiling?

Why then is there a debt ceiling? The debt ceiling appears to create inconvenience. A shut down or a default would be costly. There are likely two overarching reasons:

- The Debt Ceiling is intended to restrain government spending. If congress must ask for more money in order to fund expenditure requirements, it might discourage excessive spending. Further, it can enable opposition parties to force spending concessions, thereby mitigating a structural deficit. Ideally, this mechanism would not be necessary. However, in an environment where parties prefer to increase spending and that spending is unfunded, this can confer some discipline.

- The Debt Ceiling can force parties to work together. In so doing, it helps to avoid one party steamrolling over the other party. This is because the dominate party might be able to pass a budget, but that party might not remain in power after midterm elections. Therefore, the heretofore dominant party that wants to increase spending might have restraint imposed on it. In so doing, the debt ceiling forces negotiation.

Regardless of its merits, or otherwise, the Debt Ceiling appears here to stay. It is therefore incumbent on parties to reach a Debt Ceiling resolution. Importantly, this does not mean that parties should merely acquiesce to untrammeled spending increases. Rather, it means that the party who wishes to undertake more debt must make its case and must highlight how that additional debt is beneficial and generates economic growth without exacerbating structural deficits or saddling future generations with unproductive excessive debt.